April 2025 Newsletter

Freedom Reads: Showing Up

At the end of James Wright’s poem, “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota,” as he writes about noticing the bronze butterfly, a leaf in green shadow, as he writes about the cowbells, and sunlight between two pines, the golden stones that were once horse droppings, as he writes about the chicken hawk, I’m always utterly gobsmacked by his conclusion: I have wasted my life. And it’s such a startling end to the poem that it’s haunted me for a decade. I’m forty-four years old and watched my first sunrise less than a month ago, and now I am no more than a few hours away from when I was lying in a hammock at someone’s farm, staring at a duck with her ducklings that barely rise above the growing grass, and again I am weeping, and exhausted, and willing to admit that I have not wasted my life.

On my walk around this farm, I look for clovers of four leaves to calm myself. And time and time again I reach into the grass only to discover that what I imagine has four leaves, does not. And I know that I am farther from any prison that has ever held me captive, even as I know captive is a bit of a lie. In the moment, I just don’t want to be responsible for the night I terrified strangers with a pistol. But what of it?

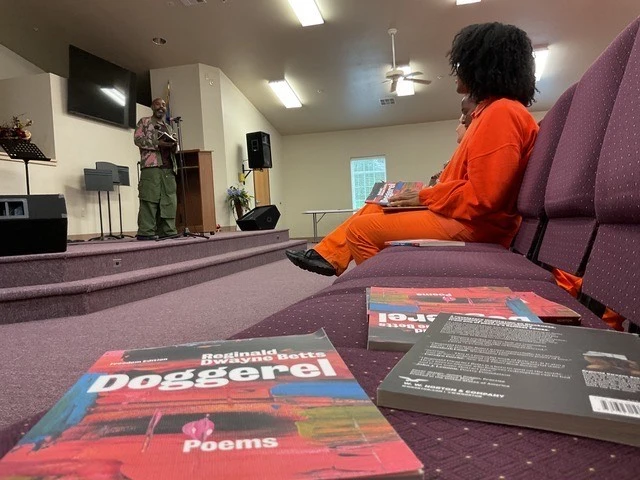

It’s the waning days of national poetry month in a nation and world starved of what poetry might offer. Three days ago, I walked into the Eddie Warrior Correctional Center for women with 100 copies of Doggerel. I had the Freedom Edition, a special edition of the book created in collaboration with W.W. Norton, my publisher. You see, when a book is first published in hardback, it means those incarcerated must wait, months or even years for it to become available in the paperback that is the only version permissible in most prisons. But I’ve collaborated with my publisher to make a special paperback edition, available simultaneously for those in prison. And I’m delighted to walk into a prison to read poems to these women.

And the room is filled with the entire spectrum of humanity always in prison. On the second row, there are half a dozen women dressed in orange and white stripes, often with a dog leash over their shoulder. They remind me of the pair of dogs standing just outside the gate, the two I imagine protect these women, women who sometimes slide the sandwiches to keep them from starving. And I know all I have is poems but believe these words too might be a kind of bread, particularly when one of the women asks her friend to stand and recite a poem. The friend does, stands up and bellows about all the ways she has come to know she matters. And someone else reminds me of all the ways that the women have suffered before getting a state number, from all manner of violence and abuse, and mostly at the hands of men. And someone asks me when did I start writing. And often, more often than I can number here, some line of my book elicits a sigh, a laugh, a chuckle. I ask them if they get the allusion in one of my poems, a pantoum called “At a Station at the Metro (Don’t You Remember)” and Ms. Vicki, who is in the back of the room with Ms. Jackson, looks at me like I better know she recognizes Luther. And Ms. Jackson tells me that I remind her of poets that saved my life: Sonia Sanchez, Lucille Clifton, Haki Madhubuti.

The women have me thinking of my mother, and several times on the stage I am bordering tears. And I swear they tell me it’s okay, again and again, as they laugh with me and let me take my time through the first three poems I’ve ever written for the woman who saved my life, a visit or letter or phone call at a time. There is so much to be said for how we forget those who save us. When my mother talks about me being in prison, she doesn’t complete her sentences. It’s as if the end of the thought is a despair she doesn’t want to announce. But being home, writing these poems for her and for all of us in any of these rooms that feel like a tomb, is to say that we can turn those rooms into a home, especially if it’s the only one we have for a time. And the women at Eddie Warrior are mothers and daughters and sisters and all of the rest of what we become because we breathe. And I hope they do not believe that their life has been wasted by the years spent in a cavern.

You’re really going to sign all our books one of the women said, and I knew she didn’t know that if I had more courage I would have spent the day with them, the weekend, that I would have returned the next weekend and the next because why should any of us be consigned to be so lonely.

People say they do not recognize me these days, and I am often believing it’s the tears that streak my face. But I should admit something. I brought a collection of poems into that prison and when I opened the book I sung as if my name was Luther or James or Aretha or Janis or Frank or my mother crooning with the voice I stole from her when I picked up a pistol in violence. I guess this is always about forgiveness and the want for it.

James Wright had it wrong. No matter where you are, if you figure out how to pause to recognize and see and feel and be lost in something beautiful, how can you say you have wasted your life.

Reginald Dwayne Betts

Freedom Reads Founder & CEO

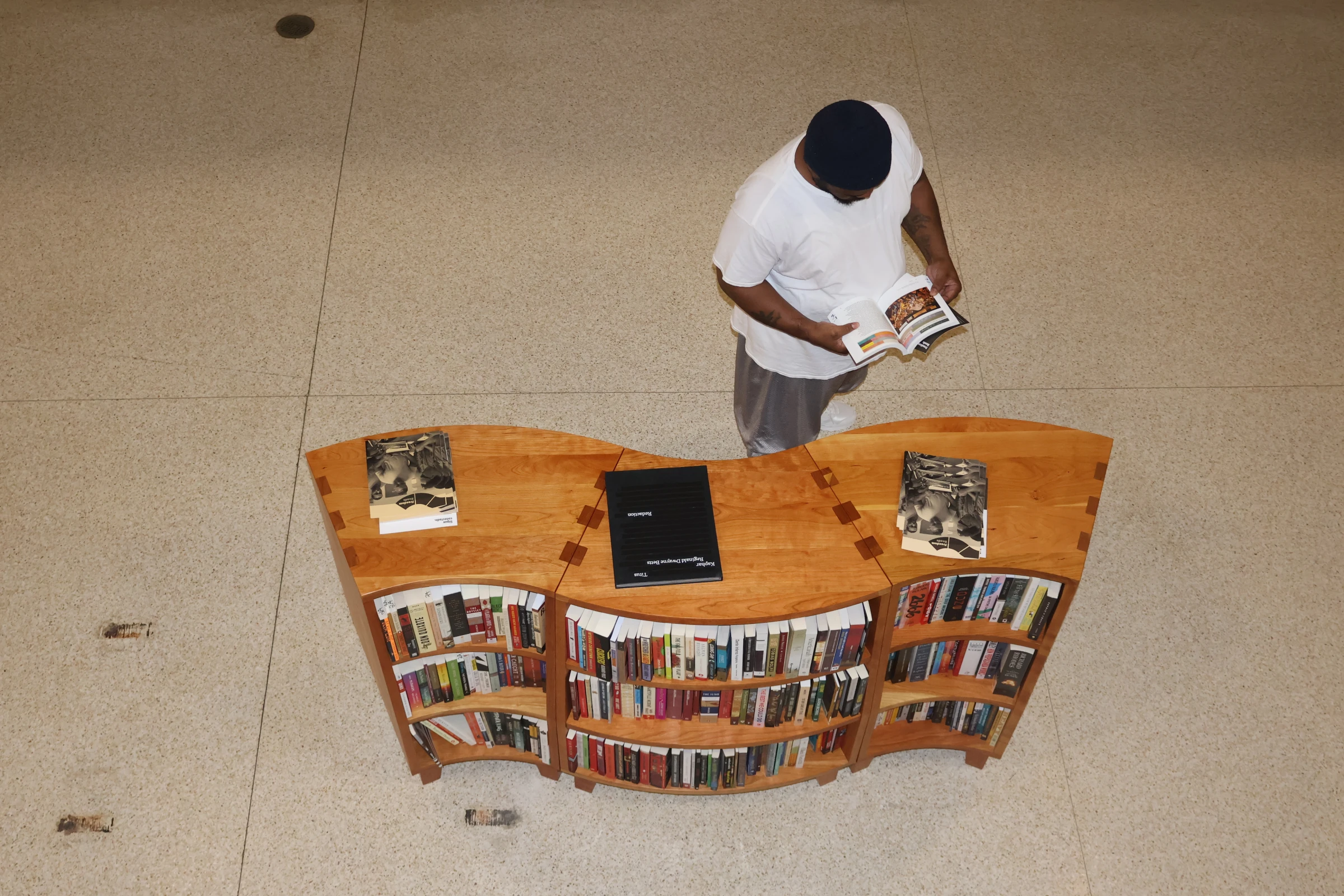

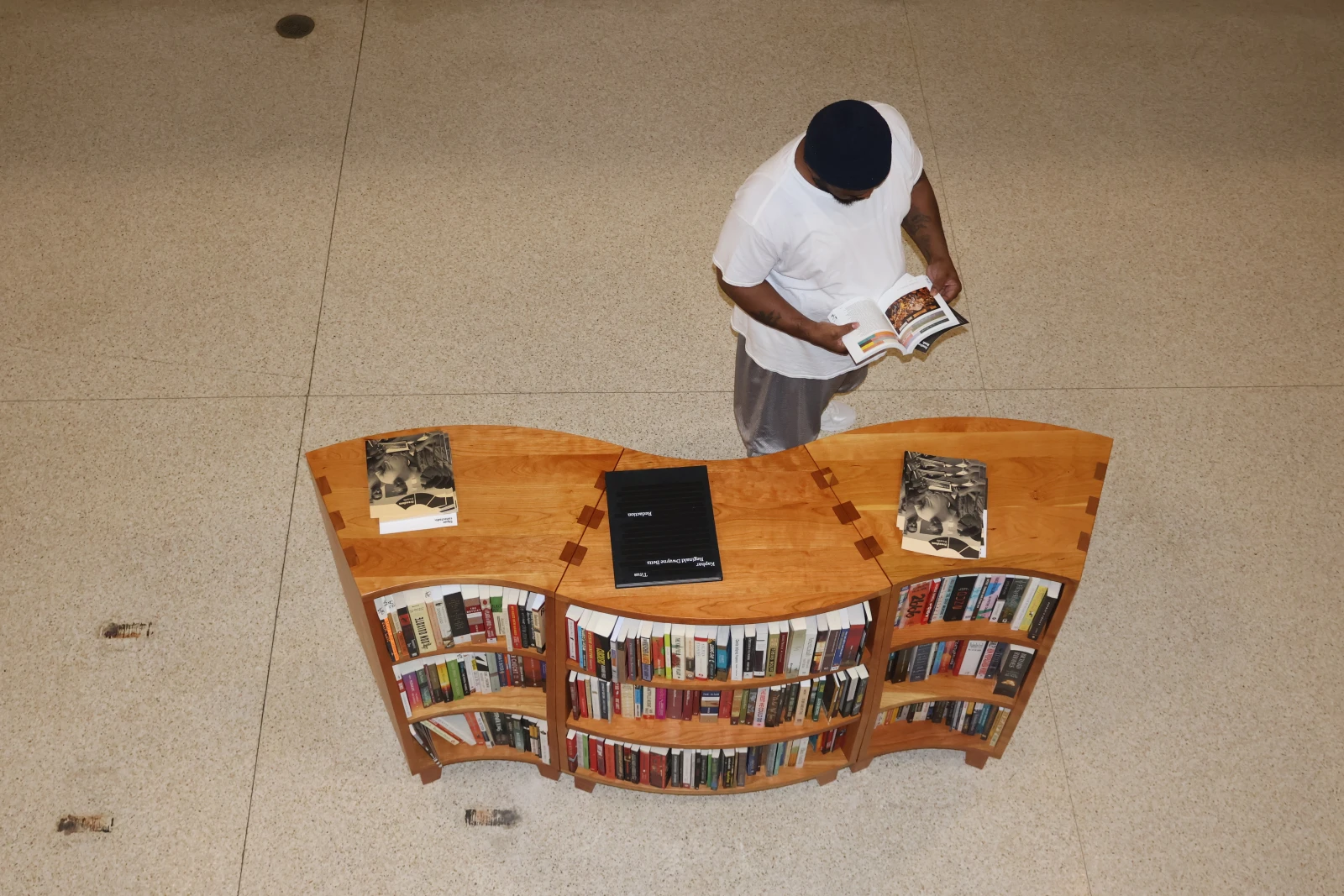

This April, Freedom Reads opened 22 new Freedom Libraries in two Illinois prisons – six Freedom Libraries in cellblocks across Decatur Correctional Center, a women’s prison, and 16 in cellblocks across Illinois River Correctional Center, a men’s prison.

To date, Freedom Reads has opened 441 Freedom Libraries in 46 adult and youth prisons in 12 states!

Freedom Reads kicked off the 2025 Inside Literary Prize tour this month at Decatur and Western Correctional Centers in Illinois. Over the next couple of months, the Freedom Reads team will bring Inside Literary Prize book discussions, voting, and author events to hundreds of incarcerated readers in 15 prisons in six states – California, Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey, Ohio, and Puerto Rico.

The judges will vote for a winner among four shortlisted titles – Chain-Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, This Other Eden by Paul Harding, On a Woman’s Madness by Astrid Roemer, and Blackouts by Justin Torres.

This month, WCIA covered Freedom Reads’ Freedom Library openings and Inside Literary Prize events across three Illinois prisons. And, Fox23 News and News on 6 covered Freedom Reads Founder & CEO Reginald Dwayne Betts' headlining events at the Tulsa LitFest in Oklahoma.

Plus, Dwayne talked about his favorite books, current reads, and latest collection of poetry, Doggerel, in The New York Times By the Book series, and Doggerel was featured in the Times’ piece on recent poetry collection releases. Dwayne also read Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Recuerdo" for The New York Times’ Poetry Challenge.

Each newsletter we aim to share at least one letter (or excerpt) from one of Freedom Reads now 37,000-plus Freedom Library patrons. Freedom Reads receives many letters from the Inside. They mean so much to us. And we respond to each and every one of them.

I wanted to reach out and say thank you again for the opportunity to participate in the Inside Literary Prize. It really helped me during a time where I was very down on myself and my situation over all. I am 12 1/2 years into a 45 year sentence and it just feels like I can't get anything positive to go my way and give myself some hope for the future.

The fact that most of you were where I am today and were able to stay the course, to come out the other side and do something so powerful is an inspiration. I feel I speak for a lot of the guys you met today that you are all doing a great service to the guys and gals in prisons across the country. Please keep this up and reach as many as you can.

Our work isn’t possible without your support. Thank you for supporting us in our vision to open a Freedom Library in every cellblock in every prison in America.